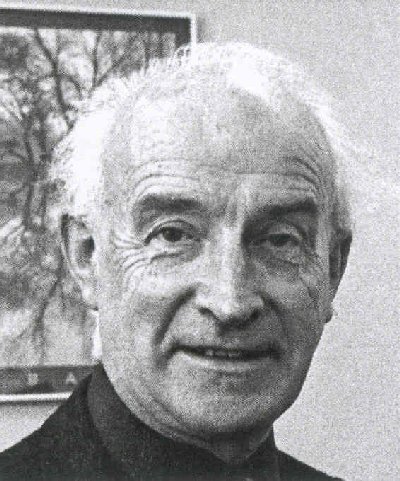

The following text was found among the late Dr John’s papers. There is no evidence as to who wrote it, and enquiries among those who knew him have failed to identify anyone. It seems to have been written about 1998, after the 1995 Festival, after the publication of Chekhov (1997) and during preparations for the 2000 Festival, which was to be the last led by Dr John. He died in 2005 – an obituary can be found here.

‘And one man in his time plays many parts’

This amazing man, now (70?) years young, has led a fascinating life – or lives, he seems to have crammed too much into his for a single life. Meeting Dr John, you have the impression of a highly energetic and passionate personality, who cares very much about a great number of things.

He qualified as a doctor in 1953 and still takes two surgeries a week. Bollington born and brought up, it is hardly surprising he went into medicine. Both his parents were doctors and his mother, Eileen, was one of 12 children, seven of whom became doctors. John remembers, as a boy, making up bottles of medicine for his father. His wife Jean is also a doctor.

His first job was on the Wirral, but Bollington soon drew him back and he has spent most of his working life in this Cheshire village. He finds the most satisfying part of general practice is the home visits. “Seeing people over a long period of time you come to know them very well. I feel responsible for a little population of my own” he says.

As well as being a well-loved doctor, John is known locally as the guiding light behind the Bollington Festival. The idea began in 1963 when it was decided to revive the many local societies which had disappeared during the Second World War. For example Bollington no longer had a Brass Band.

So the first Bollington Festival took place in 1964 with the specific intention of renewing these societies. The aim was successful, as following 1964 the Festival Choir, the Bollington Festival Players, the Horticultural Society, the Photographic Society, and the Art Group came into being.

A lot of local people helped, but John was the initiator and mentor. It was he who coordinated the efforts of the Scouts, Guides, and all the other local enthusiasts for the local groups. Very early on the organist began rehearsing ‘The Messiah’ and the schools also came in a big way. People were mobilised who had previously been struggling on their own and there was also much interest in the history of the area.

All of this is obviously very time consuming and requires a lot of energy. When I asked Dr John how often the Festival was held, he replied with a wry smile, “When the pain of the last Festival has faded”. Seriously the answer is not less than four years usually more than six years apart.

There have been lots of spin-offs. For example, the 1968 Festival led to the forming of the Bollington Brass Band. Throughout it all, there has been an increasing community awareness, and a feeling that people are responsible for their own village. When it was suggested at the first Festival, that efforts should be made for Bollington to look really good for all the visitors that were expected, John remembers that the main street, Palmerston Street, was decorated more or less en-bloc. It was difficult to walk along the pavements for all the ladders that were in the way.

When asked if he remembers any particularly interesting stories connected with the Festival, John recollects the first one. The organisers had wanted publicity and had decided to paint White Nancy white. Nancy stands guard on the hill above Bollington. Built on one of the probable sites of the bonfires that were lit across the country as a sign of warning – say at the time of the Spanish Armada – this is a stone ‘folly’. It was put up by one of the local families as a sort of shelter. Originally it had a door in the side and would offer protection for people out walking. The three farmers who owned the land around Nancy were asked for permission to paint it. Two said yes but the third, arguing that he didn’t want to attract vandals, refused. So the villagers painted two sides , but not his side. Three days later, someone slipped up in the night and painted the remaining side also. The committee got their publicity, as this story appeared in the local paper.

Some days after this, the people of Bollington woke up to find, to their amazement, that someone, again in the night, had painted White Nancy black. This story got the proposed Festival into a national newspaper – this time the Telegraph. Needless to say, by the time of the Festival it had been painted white again!

Another memory, again of the first Festival is when a gale nearly blew down the main marquee. Dr John was given this news in the middle of a surgery. His wife, Jean, exclaimed, “I really don’t know how you cope with all this”.

At another Festival, the main theme was ‘Man and Nature’. Some spectacular fossils were needed and John asked his brother, then working at Birmingham University, if he could get some. A quite rare and valuable ichthyosaurus was lent and proudly placed in a position of apparent safety. Unfortunately, when the festival was over and the ichthyosaurus was removed for returning, its nose had come off! By the time John had gone back to look for it, the marquee had been taken down. On the floor was the inevitable pile of rubbish. With little hope, but feeling that he must try, John went down on his knees to search for the ancient nose! He swept his hand through the rubble and there it was. “My delight in the rediscovery of the nose was greater than at getting the entire ichthyosaurus in the first place” he says.

When asked for his most satisfying memory of any Festival, John talks of the last one, in 1993. The people had been asked to make lanterns for themselves and to bid farewell to the festival from the top of Nancy at midnight on the final day. A choir from Spain had been invited and John went up amongst the first walkers to the sound of singing all around. When they reached the top of the hill and looked down they saw a magical sight. Walking up the hill were hundreds of people. All the pubs had emptied and folk had come out of their houses, each carrying a lantern. John recalls it was like a medieval village celebrating as, in lantern light, people greeted their friends. At midnight a powerful spotlight was shone on to Nancy as the festival closed.

The next festival will be for the millennium in May 2000. There will be a background look over the development of Bollington during the last century, and to look forward to see how it may develop over the next. As Nancy has now become such a symbol of Bollington the title will be ‘White Nancy and her children’.

The Bollington Festival Choir is probably the one spin-off from the original festival that John is most interested in. He has always enjoyed singing since his days in the school choir as a boy soprano. He had originally asked the organist at the Parish Church if he’d get a choir going which he did. They started rehearsing in the old Sunday School, but one day the organist became ill, so John took over the choir himself, having at that time no experience of conducting. It’s no surprise to discover that he learnt very quickly, and was soon conducting a professional orchestra. He took the advice ‘it’s like stirring a pudding – you have to keep the thing going’.

He finds music is great relaxation and since 1965 there have been pretty well 2/3 concerts every year. The choir has toured this country and also visited Holland, Belgium and S Ireland. There have been many visits to the Eisteddfod in Wales.

John is particularly pleased that there are still members who were there at the start. He reckons that singing in the choir gives people confidence. He says that some of their concerts have been fairly ambitious and he’s thought ‘Well, that’s a pretty foolhardy thing to try’, but it’s surprising what you can pull off.

Another exploit that John was involved in was converting the Methodist Sunday School into an Arts Centre in 1984. Funds were raised to buy it, and the building has recently been extended with the aid of a grant from the National Lottery. The aim is to bring live performances to Bollington and thus far there have been many Chamber Concerts, three Mozart operas and four Shakespeare plays, all of which John directed or acted in. In fact, he played Oberon in ‘A Midsummer Night’s Dream’.

It shouldn’t come as a surprise that this energetic man still has time to act. He says he’s always loved acting. As well as his Shakespeare parts he’s also produced Chekhov’s ‘Uncle Vanya’ and acted in it as well. “He’s one of my heroes. Like me, he was also a doctor and very keen on the stage”, he remarks of Chekhov. In fact, such is John’s interest that he has written a book, Doctor Chekhov – A study in Literature and Medicine (in his spare time?) Chekhov is one of the great dramatists of our time. Less well known is the fact that he practised medicine throughout his short life. In his book, Dr John studies this aspect of his career and the impact that it had on his literary output: taking as his starting point Chekhov’s own comment ‘Medicine is my legal wife, literature is my mistress’.

One unexpected and delightful outcome of my interview with John was that he signed and presented me with a copy of his book. An hour and a half of fascinating conversation would have been reward enough, so this was an extra bonus.

We were coming to the end of the interview and I asked, “Have you any more hobbies that we haven’t talked about?” It transpired that John is the founder member of British Hypertension Society. He is particularly interested in hypertension and has organised a major study lasting 10 years to see whether treatment in older people is effective. The answer is that it is. Proper treatment can reduce the incidence of strokes by up to 40%. This interest has introduced John to scientific friends both here and abroad.

It seemed almost presumptuous to ask, after all this, “Have you any, as yet, any unfulfilled dreams?” But yes he has. He’s trying to write the libretto of a musical about Bollington. This inspiration is a photograph of a wedding party in 1919. This set John going, finding out what Bollington was like in the summer of 1919. The musical will be called ‘Wedding Photo’. “It will be like ’Under Milk Wood’ but for Bollington”, he explains.

When asked the question “What is the most satisfying thing you have done?” the answer came “That’s very difficult, but probably the thing I’m doing at the time”. He does however recall conducting Verdi’s ‘Requiem’. “I felt totally overwhelmed by the experience. I feel it a great privilege to have lived a life that made that possible”, he talks of his debt to other people and how he has leant on their creativity. With modesty he adds “I’m pleased and proud to have been part of a community like this”.

Thanking him for his time, I was packing up and getting ready to leave when, by chance, I commented on one of the brightly coloured puppets that were hanging around the room. He had made no mention of them and I had just assumed that they belonged to his wife. “Oh they’re mine” he said. He collects them from all over the world and has about 100. Once in India he was introduced as ‘John Coope, the puppeteer from England’. He took me through a corridor where many more puppets were hanging and into a room which contained a lovely little puppet theatre. Here he puts on plays which he has written himself for his nine grand-children. What for anyone else would be a major hobby had been forgotten about, such being the wealth of all his other interests.

Another thing that John didn’t tell me about until I mentioned it first is the fact that the grateful people of Bollington have named a street after him on Bollington Cross. But well done, John, you certainly deserve it.

Acknowledgement

We acknowledge with many thanks the contribution of Geoff Atkin who has transcribed the original document and tried to identify the author. If you wrote this most excellent piece, please contact the webmaster via the contact form link in the footer below.