Gas was the first utility service in the town, Gas was the first utility service in the town,established by a local Board of Health in 1862. There was no public water supply, and human waste was removed from private closets by the night-soil men until after Bollington Urban District Council (BUDC) was created in 1894. The mains water supply from a bore hole at Rainow was established in 1899, and the waste water system in 1906 with a works at Lowerhouse, where the now closed recycling depot was located. |

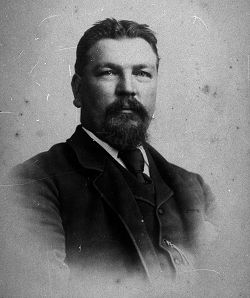

Pictured left is Henry Froggatt, for a long time the Superintendent of the gasworks.

Pictured left is Henry Froggatt, for a long time the Superintendent of the gasworks.

Some of the mills, such as Oak Bank mill, had their own gas production units but these would have been entirely in-house facilities producing gas for both processing (‘gassing’*) and lighting, and quite incapable of providing a public service. The public gas supply was provided from a gasworks in Princess Street (parallel to the lower end of Grimshaw Lane). This works contained a retort where the fuel coal was heated to drive off the gas, known as ‘coal gas’ or ‘town gas’. What remained was coke, which was a valuable energy source in its own right, and tar, and both could be sold. Various processes were used to purify the gas, before it was pumped into one of two gas holders to be stored – the two big round objects towards the bottom of the picture. The public supply came from these gas holders and was distributed through the town in pipes laid under the streets.

This service continued until the 1960/70s, when ‘natural gas’ arrived, piped from wells beneath the North Sea. Once the town gas was no longer required only the gas holders would have been retained to provide local storage, but these, too, became unused and the gasworks was demolished. Houses were built on the site in the early 2000s, Spinners Way today.

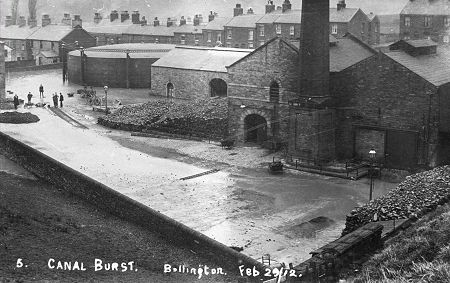

The gasworks suffered serious interruption when the Macclesfield canal breached at Tinkers Clough during the night of 29 February 1912. There was considerable flooding of the gasworks and the retort fires were extinguished.

The gasworks suffered serious interruption when the Macclesfield canal breached at Tinkers Clough during the night of 29 February 1912. There was considerable flooding of the gasworks and the retort fires were extinguished.

Gasworks require a continuous supply of large quantities of coal. Bollington gasworks was located adjacent to the railway goods yard, and yet there was no direct connection between the two. Coal would have been unloaded from railway wagons into horse carts and taken more than a quarter mile via Grimshaw Lane, Henshall Road, and Princess Street, to be unloaded no more than 100m from the railway yard!

There was some gas powered street lighting in Bollington – see below. This was one of the first uses for gas in this country. We would like to know of any further evidence of this. There used to be a frame to support a gas lamp on a house at the top of Grimshaw Lane, but that has gone now. There is just one remaining gas street lamp in use locally – the gas lamp outside the half-timbered house at the road junction in the middle of Pott Shrigley. This ancient lamp is retained and always lit! There are two in Moss Lane, Lowerhouse, converted to electricity – see the story below.

* Gassing – a gas flame was used in the cotton mills to burn off the whiskers from the cotton thread to produce a cleaner and more shiny product.

Death of Thomas Wright

There is a report in The North Cheshire Herald dated June 8th 1878 regarding the unfortunate death of one Thomas Wright at the gasworks. Apparently he swallowed, and was poisoned by, carbolic acid, better known today as phenol![]() . This substance was a very effective anti-septic, but dangerous, exposure resulting in chemical burns. The Coroner’s Court, with jury, returned a verdict of accidental death. The coroner also advised that the bottles of carbolic should in future be labelled ‘Poison!’.

. This substance was a very effective anti-septic, but dangerous, exposure resulting in chemical burns. The Coroner’s Court, with jury, returned a verdict of accidental death. The coroner also advised that the bottles of carbolic should in future be labelled ‘Poison!’.

I recall that my father, a dairy farmer, used the same carbolic acid in the 1950/60s for cleaning the milking equipment. It was supplied in a carboy which was a glass or pottery container, globular in shape and contained within a metal mesh box shaped frame stuffed with straw to protect the bottle. The whole thing was so unwieldy that one needed to decant the acid into a smaller container for daily use – a great opportunity to spill or splash the acid! I suspect that in the Wright case the acid had been decanted into a conveniently available bottle such as a beer or lemonade bottle and poor Wright had failed to realise what it contained before attempting to slake his thirst. In the local council Board meeting following this accident one member suggested that Wright would have been suffocated rather than poisoned because the gas coming off the acid would have prevented him from swallowing it.

I am most grateful to John Cross for bringing this story to my notice.

Lowerhouse Gas Lamps

Our considerable thanks to Harold Skelhorn, long time Lowerhouse resident, for his memories …

In January 1962 we moved into the School House on Moss Lane, Lowerhouse. We hacked our way through the hedge to gain access into our heavily overgrown garden.

In January 1962 we moved into the School House on Moss Lane, Lowerhouse. We hacked our way through the hedge to gain access into our heavily overgrown garden.

In April or May 1962 workmen from the north west Electricity Board arrived, and set up the tea making brazier in our garden on what to them looked like waste ground, unloaded a drum of underground cable and set about installing the cable through our garden to the footpath at the back of the house. This work was to replace the old gas lamp with a new concrete electric lamp. Agreement had been reached with the previous owner of the house for this work to take place. I made a new deal with the team, allowing them to continue the installation by leaving me the old cast iron gas lamp and getting cinder from the mill to repair my garden foot path after completion.

There were six cast iron gas lamps still working in Lowerhouse at that time, along with about twelve more coming down the right hand side of Albert road, all due to be replaced with the new concrete electric lamps.

Over the front door of School House, just above an engraving: LOWER-HOUSE LIBRARY 1862, is a cast iron bracket holding the original Victorian gas lantern that I restored and converted to electricity in 1962, 100 years after the house was built.

Over the front door of School House, just above an engraving: LOWER-HOUSE LIBRARY 1862, is a cast iron bracket holding the original Victorian gas lantern that I restored and converted to electricity in 1962, 100 years after the house was built.

The gas lamp post I was given, with its copper lantern missing, weighs over 1000kg. Moving it became an engineering challenge. Time passed leaving it standing alongside the new concrete electric lamp on the path at the back of the house, until 1979. 0ur three sons were about to leave for university, and we came up with a plan to move the lamp before they went, and install it at the front of the house on Moss Lane.

Acknowledgements

Our thanks go to those who researched and discovered the history that is presented in these pages. Please read the full acknowledgement of their remarkable achievement. Unless otherwise noted, the historical pictures are from the Civic Society picture collection at the Discovery Centre .

Special thanks go to Harold Skelhorn for his history, and pictures, on Lowerhouse gas lamps.

Your Historic Documents

Please don't chuck out those historic documents and pictures! Find out why here.