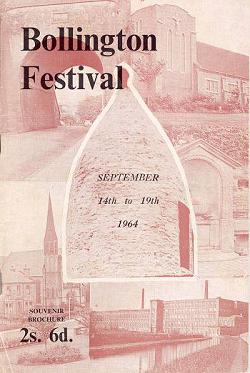

The first festival was held in 1964, instigated by Dr John Coope, whose intention was to bring together a community being seriously damaged by the new freedoms unleashed in the 1960s. Dr John got together a group of like minded people and they formed a Festival Committee and put on a quite unique event in September of that year.

The first festival was held in 1964, instigated by Dr John Coope, whose intention was to bring together a community being seriously damaged by the new freedoms unleashed in the 1960s. Dr John got together a group of like minded people and they formed a Festival Committee and put on a quite unique event in September of that year.

The considerable success of this first event led Dr John to propose a second festival in 1968. Over the years since there has been a whole series of festivals, each often bigger and more ambitious than previously, always massively successful.

Festivals have been held in 1964, 1968, 1974, 1980, 1986, 1993, 199?, 2000, 2005, 2009, 2014 (to remember the fiftieth anniversary of the first), and 2019.

A Written History

When Dr John Coope died (2005) his family very kindly donated a large collection of his papers to the Civic Society. One of those documents was a hand written history of Bollington Festival, written by Kathryn Kirby in 1980 after she followed the progress of the planning and implementation of that year’s festival. We don’t know who Kathryn is or where she is today. I have had her name on a page of sought for people for several years but, alas, without result. I have now decided to publish her very interesting paper for the benefit of a very important aspect of Bollington history. Her paper is divided into a number of pages and begins here …

The Bollington Festival

Written by Kathryn Kirby PG Dip. Lib. 1980.

Introduction

This year [1980], Bollington in Cheshire, a small community affectionately known locally as ‘The Happy Valley’, held it’s fourth festival in celebration of village life and culture [Festival T-shirt, right].

This year [1980], Bollington in Cheshire, a small community affectionately known locally as ‘The Happy Valley’, held it’s fourth festival in celebration of village life and culture [Festival T-shirt, right].

Twentieth Century Britain has witnessed a resurgence of the festival spirit, reminiscent of a bygone age when Medieval villagers danced and processed to the accompaniment of lutes and viols. There are the large international festivals which occur annually, festivals to celebrate a specific historical event, such as the granting of a town’s charter, festivals and street parties in honour of occasions of national pride – notably Britain’s victory in the second world war and, more recently, the Queen’s Silver Jubilee – and festivals organised by local communities purely for the enjoyment and entertainment of their visitors and themselves.

The Bollington Festival belongs to the last category. Since the Festival Movement began in 1964, it has presented an opportunity for Bollingtonians old and new to join together once every four or six years in a fortnight of festivities embracing music, drama, sport, arts and crafts and dancing.

The reasons why I have chosen to look in depth at one particular village festival rather than one which is internationally acclaimed, such as the Edinburgh Festival, are threefold – In the first place, I hoped, through living on the periphery of Bollington, to be able to attend more activities than would otherwise have been the case – Secondly, I was very interested to see how closely the villagers identified themselves with the festival activities – a successful festival depends upon strong commitment from participants as well as from the organisers. Finally, village life at its best, with its strong community spirit and friendliness, seems to me to epitomise all that festivals stand for.

Methods & Sources Used

While I found two publications on the history of Bollington[1] useful in providing an account of the growth and development of the town, most of the information for this project has come from interviews with organisers of the Festival, in particular Dr John Coope, the Festival Chairman, who very kindly answered many questions about festival organisation, from personal observation and from the Festival Brochure, programme notes and newspaper articles. I have also made quite extensive use of photography to illustrate the ways in which the festival was publicised and promoted and to indicate the breadth of activities during Festival Fortnight.

Organisation of material

The project has been divided into seven sections, beginning with a short historical survey of Bollington and the Festival Movement. In the following sections, various aspects of the 1980 Festival are highlighted – planning and preparation, publicity, the Festival itself, the Granada Television film entitled ‘Small Available Joys’ which featured Bollington at Festival time, achievements of the Festival and lessons learnt for the future, and finally, some general conclusions which may be drawn about the planning and organisation of a village festival.

An historical survey of Bollington and

the origins of the Festival Movement

Little is known of Bollington before the nineteenth century, except that it was a small agricultural community and that its close neighbour, Kerridge, possessed coal mines which had been worked spasmodically since the Middle Ages. Bollington’s rapid development during the nineteenth century from a village of 1,200 inhabitants in 1801 to a town of 4,600 people in 1851 was a direct result of the Industrial Revolution. Cotton, along with stone, became a major industry and mills were built in various parts of the town, beginning with the Waterhouse Mill at the end of the eighteenth century. The construction of the Macclesfield Canal in 1831 encouraged the building of more mills, including the Clarence in 1830 and the Adelphi about 25 years later, both of which were sited in close proximity to the canal. By the mid nineteenth century, cotton and stone flourished where only a few years previously agriculture had held sway.

Special mention should be made of the Greg family who made a significant contribution to the community. Samuel Greg [Jnr] came to Bollington from Wilmslow in 1832, at the age of twenty eight, to take over the empty Lowerhouse Mill. A great idealist who had studied the conditions at his father’s works at Quarry Bank, Styal, he wrote to the Inspector of Factories that he:

“aimed to show to my people and to others that there is nothing in the nature of their employment or in the condition of their humble lot that condemns them to be rough, vulgar, ignorant, miserable or poor; that there is nothing forbids them to be well bred, well informed, well mannered and surrounded by every comfort and enjoyment that can make life happy.”[2]

He named the town ‘Goldenthal’ – The Happy Valley. Although he later alienated his workers by attempting to introduce machinery for stretching cloth and for the rest of his life ran the business from his home[3], never again venturing to the mill, there were many testimonies to his goodness and integrity.

In 1876, another member of the Greg family, Francis Greg of Caton, Lancashire, came to Bollington and later generously presented to the people of Bollington the Recreation Ground which now is not only used for cricket, football and bowls but also plays a central role in the Bollington Festival, housing the marquees which together form the Festival Centre.

By 1851, the town had ceased to grow rapidly and had assumed its present appearance, becoming one town rather than, as before, a collection of district hamlets. Despite the influx of ‘immigrants’ from surrounding villages in Cheshire, Derbyshire and Staffordshire and, on a small scale, from Ireland, Bollington managed to adsorb the newcomers without degenerating into an overcrowded ‘slum’ area – the unfortunate fate of some of the Lancashire cotton towns – and, in fact, the population remained stable for the next hundred years, not beginning to rise again until the 1950s.

Bollington’s importance as a manufacturing town was enhanced by the opening, in 1870, of a railway line from Macclesfield to Manchester via Bollington. For the next hundred years, it provided a link between Bollington and the port of Manchester as well as bringing to ordinary Bollingtonians the possibility, for the first time, of travel to other towns and seaside resorts, particularly during the annual Wakes Week when the mills closed down.

Economic reasons finally brought about the closure of the railway in January 1970.

Apart from the severe hardship caused by the cotton famine of 1861-64 – a consequence of the American Civil War – the cotton industry flourished in Bollington, as elsewhere, until the years of the recession in the 1930s. After the Second World War, the industry enjoyed a temporary recovery but in the 1950s Bollington, in common with other towns in the North West, began to witness the gradual closure of her cotton mills, including the Waterhouse Mill in 1960, the Clarence in 1970 and the Adelphi in 1974. Just as cotton replaced agriculture as the main industry in the nineteenth century, so cotton has, in its turn, been superseded by younger, more vigorous industries such as light engineering and rubber and plastics technology.

Although the livelihood of Bollingtonians has changed substantially in recent years, certain buildings in and around the village link Bollington Past and Present, not least the churches and pubs! Slater’s ‘Lancashire and Cheshire Directory’ of 1855 lists eleven public houses, all of which, with one exception, still offer hospitality under the same sign today. Eleven ‘retailers of beer’ are also listed, making a grand total of twenty-two – the same number as exists in Bollington and Kerridge at the present time [1980]. Of the eight churches in the village, all but St. Gregory’s (1957) were built during the nineteenth century.

But perhaps the most symbolic – certainly the most romantic – link between Bollington Past, Present and, one hopes, Future, is the small white cairn, known as ‘White Nancy’, which stands on Kerridge Hill, overlooking Bollington and the surrounding district. Exactly why it was built is not known for certain, but it is thought that it was built by a member of the Gaskell family of Ingersley some time between 1815 and 1818 – possibly to commemorate Waterloo. One of the first printed references to White Nancy appears in a history of Macclesfield published in 1825 by several gentlemen of the time –

“Still advancing ere long, you will be near the top of the Ridge which parts Bollington and Rainow. At the summit you will find erected by the late Mr. Gaskell, a round building, clothed in white, called Northern Nancy.”[4]

The origin of the cairn’s name also remains a mystery. Perhaps the name ‘Nancy’ was intended to remind villagers of two ladies, Nancy Gaskell of Rainow and her daughter, also called Nancy. Another suggestion is that the name is a play on the word ‘ordnance’, a reference to the old ordnance beacon that once stood on the site. What is certain, however, is that White Nancy has been known and loved by several generations of Bollingtonians and keeps a watchful eye over all their activities from her commanding position above the village. In the past, she has presided over celebrations for Coronations, victories and jubilees and, more recently, over four Bollington Festivals, being chosen as the stage for the magnificent firework displays on the opening night and featuring in the title of the Bollington Festival Committee’s booklet on nineteenth century Bollington[5] – a sure sign of the village’s affection.

References

Clicking on the text below will take you back to the point of reference.

- Bollington Festival Committee, ‘When Nancy Was Young’ 2nd ed., 1980

Broster, W.S., ‘Bollington and Kerridge 1830-1980’, 1980- Extract from a letter of Samuel Greg. Bollington Festival Committee, ‘When Nancy Was Young’ 2nd ed., 1980 p.21

- Editor’s note: He actually handed the management of the business over to a relative.

- Bollington Festival Committee, ‘When Nancy Was Young’ 2nd ed., 1980 p.1

- Bollington Festival Committee, ‘When Nancy Was Young’ 2nd ed., 1980