A short history of Bollington

For many thousands of years Bollington was blessed with no history to speak of being an obscure part of the Parish of Prestbury. Exciting and imaginative stories can be created about Archers at Agincourt and wild hunts through the Forest of Macclesfield or visits from the Black Prince. However, until the 17th century, our little valley with its river Dean, fed by Harrop brook, running through rocky bank, marsh and open fields saw no more than the common activities of rural England: sheep and cattle farming, domestic farm activities, wood cutting, charcoal burning, together with some stone cutting and surface coal mining.

The only outsiders were itinerant traders in salt, coal and peddlers wares using ancient tracks dating from Roman times and before, in some places hard now to define. The best attested is the one leading up Hedgerow in Harrop Valley and out over the Hill to Kettleshulme and beyond. There is another that possibly came into Bollington up Clarke Lane and Redway and up the east side of Kerridge to Rainow and beyond. Traveling preachers probably stopped at Bollington Cross on their way to the north. The Cross has been seen in living memory but now has disappeared and we are not sure where it was placed. A new cross was erected to mark the millennium.

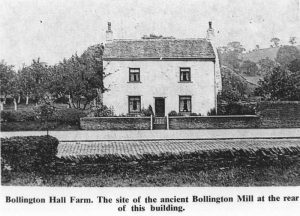

The earliest buildings to survive are all connected with day to day agricultural living; the farmhouse which is now the Bridgend Centre![]() , Bollington Hall Farmhouse (right) the white house between the Post Office and Albert Road, with the plaque, with its remnants from the Tudor period, and the low set house, Throstles Nest, opposite the Bridgend Centre in Palmerston Street all have their origins in the early post middle ages. The oldest is probably Sowcar Farm (actually in Rainow parish) opposite the Poacher’s Inn.

, Bollington Hall Farmhouse (right) the white house between the Post Office and Albert Road, with the plaque, with its remnants from the Tudor period, and the low set house, Throstles Nest, opposite the Bridgend Centre in Palmerston Street all have their origins in the early post middle ages. The oldest is probably Sowcar Farm (actually in Rainow parish) opposite the Poacher’s Inn.

With the gradual clearances of the woodland and the extension of arable and sheep farming over the centuries a pattern of farm ownership grew up based on local large land owners. By the 17th century farms such as Old Hollin Hall at the top of Hurst Lane and Stake House End Farm in Chancery Lane, Ovenhouse Farm on Henshall Road and the farms in the Dean valley above Ingersley Vale were all settled and thriving.

By the end of the 17th century Bollington was still a series of farms with possibly a concentration of buildings at Bollington Cross. Some ordinary cottages here have early remnants in their interiors. The Great Civil War 1642-46 passed us by. There was a skirmish at Adlington in 1643 between Manchester Parliamentarians and Royalists. The Roundheads lost but soon after Cheshire was held for Parliament and retained in spite of the incursions of Prince Rupert in 1644.

With the rise of the silk industry in the Macclesfield area in the 18th century the picture of rural peace was shattered by the beginnings of the mighty changes that were to bring to birth in the 19th century the exciting industrial community whose architecture surrounds us today. It is difficult to believe that Bollington’s agricultural workers and quarry workers families were not involved in the making of silk buttons throughout the 18th century as this was a major village activity based on the merchants of Macclesfield.

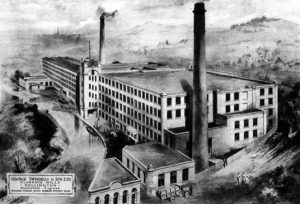

What is clear is that during the latter part of the century many water mills began to appear in Rainow and Bollington. The Adlington Estate made a complaint to the Court of Chancery in 1805 that these numerous mills were taking all their water. But the industry that changed the face of the town was cotton and the people who changed the face of the town were the great mill builders and cotton manufacturing families such as Philip Antrobus, Peter Lomas, Thomas Oliver and his descendants, Joseph Brooke, the Swindells father and sons, and the Gregs. The end of the Napoleonic wars had brought about an industrial slump in the north of England. Then the beginnings of free trade after an Act of 1826 brought about another slump. In the early 1830’s business began to revive and we see a spate of activity in the town.

Lowerhouse mill built in 1818 by the Antrobus family was taken over by Samuel Greg and opened as a cotton mill in 1832. Samuel Greg was a social pioneer who created a model industrial community from 1832 to 1846, that became known as Goldenthal or Happy Valley. It was the fate of his community that is believed to have inspired the industrial novels of Elizabeth Gaskell, Mary Barton and North and South.

It was the Swindells family who dominated the cotton town. They occupied or owned with various partners Ingersley Clough mill (now ruined) and Rainow mill (long gone, but was where the green industrial shed is today at the junction of Mill Lane and Ingersley Vale) from 1821 to 1841, Higher mills (disappeared under Dyers Close) and Lower mills (now Tullis Russell) from 1832 until 1859 and Waterhouse mill in partnership with Thomas Oliver from around 1832 until 1841.

The Swindells family made their lasting contribution to the town’s architecture when, with partner Joseph Brooke, they built Clarence mill in 1830 and the next generation built Adelphi mill in 1856 taking full advantage of the newly opened Macclesfield Canal in 1831 whose stone bridges, aqueducts and wharves were engineered by William Crosley. Thomas Telford had surveyed the route. These magnificent industrial buildings are still with us, albeit metamorphosed by developers into flats and business units. The original owners brought raw cotton in through Liverpool from the U.S. and exported finished products to the world through agents in Manchester. They were the leaders of a globalised industry. There are Swindells monuments in St. John’s graveyard including a moving memorial to the wife of Martin Swindells.

It was the wealth of the cotton industry that created the mills and cottages of upper Bollington and some of the splendid family homes such as the Oliver’s family residence, the Waterhouse, now part of the Medical Centre and a private residence. There are two wonderful sculptures by Alfred Gatley, Bollington’s famous 19th century sculptor depicting Martin Swindells and his wife, Elizabeth. It was the crises in the cotton industry that brought hardship and uncertainty into the lives of our townspeople in the nineteenth century. There are the graves of young children in St. John’s churchyard who suffered and died due to poor public health provision and lack of medical care that accompanied the growth of private wealth. Outbreaks of cholera were not unknown, even up to the beginning of the 20th century. Only the development of public services for clean water, waste water and rubbish disposal, and gas supply, brought this to an end.

The remaining distinctive characteristics of the town were created by the 19th century transport revolution. The first canal into Macclesfield was proposed by the Brocklehurst family in the 1760’s. Francis Egerton, Duke of Bridgewater, put a stop to that, wanting to maintain his monopoly on water transport. The Trent & Mersey Canal Co, were equally difficult in later years, thus the development of the area was held back for 70 years until the canal was opened in 1831.

Once the Macclesfield Canal was built, linking the Peak Forest Canal at Marple to the Trent & Mersey Canal at Kidsgrove, cotton, coal, stone and general goods could be much more easily transported. A tramway was constructed from Endon quarries on Kerridge Hill to the canal side at Kerridge dry dock as well as the great mills being built. The soaring aqueduct over Palmerston Street and its lesser brother over Grimshaw Lane are testimony to the engineering skills of the 19th century.

The railway took some time to come to Bollington and lasted a century from 1870 to 1970. It is now the Middlewood Way cycle and walking track and the goods station and sidings is now the Clough Bank transport and industrial park. The business units on Grimshaw Lane replaced Joseph Wetton’s stone yard. The passenger station was beside that.

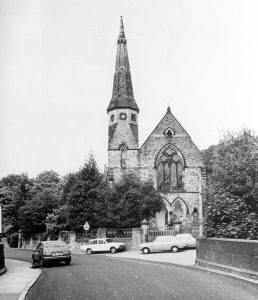

As we have said, for much of its history Bollington has had a corporate identity as part of the Parish of Prestbury but in the 19th century the town grew so populous that it justified its own Parish with the building of St John’s church in 1834. The Methodists had built the first church in 1807 followed by another and then the present handsome church and manse opposite the Town Hall. The Anglicans and Catholics followed in 1834 with the church of St. John and the first St. Gregory’s Chapel (now gone) built on land in Chapel Street given by Sir William Turner of Shrigley Hall. The present St. Gregory’s is a handsome brick built building next to the viaduct on Wellington Road. St. John’s church was closed in 2003, followed by Holy Trinity in Kerridge, and now Anglicans worship at St. Oswald’s at Bollington Cross next to the Church of England Primary School.

There was a primitive Methodist church in High Street now disappeared and replaced by High Court. The Congregational Church (right) opposite the Bridgend Centre![]() has been cut in half and turned into offices and a close of modern houses, Church Mews. There was a further Methodist church (tin tabernacle) on Rose Bank, off Grimshaw Lane, and another in Kerridge.

has been cut in half and turned into offices and a close of modern houses, Church Mews. There was a further Methodist church (tin tabernacle) on Rose Bank, off Grimshaw Lane, and another in Kerridge.

In the 20th century, Bollington avoided war damage in the physical sense. However, the town experienced a long slow decline in the textile industry, coupled with the rise of private transport, and out of town shopping gradually drained work and commercial activity from the town. Nevertheless, Bollington Urban District Council had a proud history of providing community facilities such as piped water and gas and the corporate life of the mills and churches supplied ample excitement in fetes, parades, sporting events and away days in Wakes Weeks. New houses were built of stone in the 1930’s and brick in the 1950’s.

However, from the 1990’s onwards Bollington has enjoyed a renewal of life based on its picturesque position on the edge of the Peak District surrounded by green belt, but in easy reach of good employment centres like AstraZeneca, Manchester Airport and large urban areas such as Stockport and Manchester. There has been a continuous inflow of people and the ever present blue boards of Holmes Naden are evidence of continuing mobility.

Some large businesses survive, notably Slater Harrison at Lowerhouse mill and Tullis Russell at Lower mill both producing specialist coated papers. New businesses have developed in the pharmaceutical and financial sectors, transport, silk printing, paper printing and advertising. The internet revolution has enabled home-working to grow. The stone cottages that used to house large families of industrial workers, now modernised, are highly valued by single people and young couples. This pressure is indicated by the price of an average cottage moving from £40,000 to £120,000 over the 10 years 1995-2005.

The town has been particularly fortunate in the input of the Coope family in medicine and the arts. The late Dr. John Coope MBE was responsible, with a number of other talented individuals, for the founding of the Bollington Festival as well as the creation of the Bollington Arts Centre![]() in the former Methodist Sunday School.

in the former Methodist Sunday School.

Bollington Civic Society has masterminded the creation of the Bollington Discovery Centre in 2005 which is dedicated to informing the people of the Town as well as our visitors of the complex history of this small but vibrant community.

The Town enjoyed independent Civic Status from 1894 until 1974 as the Bollington Urban District Council. Many regret the town’s loss of local powers. We hope to see its Civic Spirit continued as the Bollington Town Council works to build a better future for a strong and safe community through the implementation of the Parish Plan adopted in 2004, updated in 2008, and then the Neighbourhood Plan in 2018. In doing so the Town Council is pledged to work with all the other groups in the community to ensure that the 21st century, like the 19th and 20th, is one of enterprise, energy and hope for the people of Bollington.

Ken Edwards

April 2005 (with later minor updates)