Stone | Coal | Fireclay / Shale

Stone

The demands of mill and house builders in the town meant that a ready supply of stone was essential for the rapid development of Bollington. Fortunately, there is a source of very good building stone just beneath the surface, and many quarries were opened up on both sides of the valley of the river Dean, as well as all along Kerridge hill. In Bollington there was:

- Beeston, on the north side behind Queen Street, Oak Bank mill, and extending towards Nab hill;

- Hurst, on the south side behind Water Street;

- Owlhurst, and many smaller quarries.

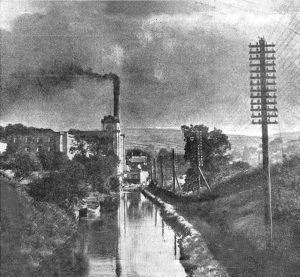

In Kerridge, there were many stone quarries, particularly along the west side of Kerridge hill (pictured). The stone was very high quality and in demand for the facing of public buildings around the country:

- Bridge – previously Victoria quarry (1851), Bridge End quarry (1871). The Victoria incline and the Rally Road were used to transport stone from Bridge Quarry down to waiting boats on the canal.

- Sycamore (or Green’s), Northend, Windmill, Five Ashes, Glory Hole, Albert, Orme’s, Gag, Marksend, Endon.

There is a good article on the subject, Rock of Ages, in Bollington Live!, March 1997 p.13![]()

Edward ‘Ted’ Allen (b.1907 d.1958), (Webmaster Linda Stewart’s grandfather) was a stone mason. He owned one of the quarries on Windmill Lane. Although all the local history attributes the making of the ball on top of White Nancy to one Tommy Cooper it was in fact Ted who made it. Tommy Cooper was chairman of Bollington Urban District Council at the time, and told the members he could make it. When he tried to carve the new ball it cracked in half. Ted, who was a fine stone mason, made a replacement, and Cooper took all the accolades!

|

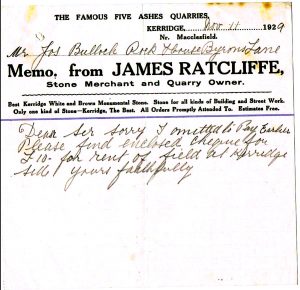

The ‘Famous Five Ashes Quarries’ (left) were also on Windmill Lane. In the field beside the houses at Five Ashes there is much evidence of industrial activity including quarrying. About 100m along the road from the houses there is a low ‘doorway’, just an opening into a little room. This was a lime kiln which would have been fed through an opening in the top, now closed, and emptied through the opening onto the roadway. Lime kilns are normally located next to either a supply of limestone or of coal. In this case coal which would have come from the seams under Kerridge hill. The limestone would have come a greater distance, perhaps from the Peak District. |

Coal

As the town developed so the demand for coal increased enormously. It would be needed to fire the boilers at many mills, especially once they moved from water power to steam power. Oak Bank mill used 250 tons a week! Add to that the needs of domestic users – the coal fired range was the sole means of heating and cooking in most homes. However, while there were large numbers of pits around the town they produced relatively little coal and it is believed that few of them were profitable for their developers. The quantities of coal consumed in Bollington required much of it to be brought in by canal from Higher Poynton and Macclesfield pits.

There were many small coal pits in the district and the remains of many can be seen along the east and north sides of Kerridge Hill. Some of these pits were bell pits – a hole was dug down to the coal seam, then the coal was removed and the bottom of the hole got ever wider, until it started to fall in, at which point the pit was abandoned and a new hole dug a short distance away. Other pits were based on a shaft dug into the hillside following a seam of coal. Also still visible are the tracks that connected these pits together and to the roads to enable the coal to be taken away from the hill. Some tracks are today used as footpaths, others are just marks along the hillside.

The biggest pit in Kerridge hill was on the west side and developed by William Clayton. This pit had shafts and galleries. There was also a tunnel through the hill to access pits on the east side. A feature long believed to have been a ventilation shaft which stands beside Windmill Lane by Victoria Bridge is thought to have been built by William Clayton. However, it was re-furbished in 2009 as part of the KRIV project and found to have a solid rock bottom, so it is unlikely to have been for ventilation. Neither did it have any soot inside so it could not have been a chimney for any industry lower down the hillside. It’s purpose remains a mystery – perhaps it was just a folly, a big proud and impressive structure easily visible to Clayton’s peers as they approached the town from Manchester, Stockport or Macclesfield!

Fireclay / Shale

Usually mined with coal, seams of fireclay and shale were to be found under Bollington and stretching to Pott Shrigley and Bakestonedale, all part of the wider Poynton coalfield. The coal and the fireclay were usually one above the other so it made considerable economic sense to mine them both, make bricks of the clay and fire them with the coal. This was how it was done at William Hammond’s brick works at Pott Shrigley.

Just north of Clarence mill, along the canal a couple of hundred metres, there is a wharf. If you look carefully you will see that the off-side canal edge is formed from large well dressed blocks of stone. This wharf belonged to John Hall & Sons Ltd and served their mine, the drift shaft of which can still be seen, easiest in winter, alongside the field hedge about 150m from the canal. This gently sloping shaft went back under the hill and the output was fireclay and shale – both more valuable than the coal. This was loaded onto day boats (those having no living accommodation) at the wharf and, at one time, about 100 tons per week taken to Dukinfield near Ashton-under-Lyne, to the east of Manchester. So imagine, if you will, the lot of the poor boatman – he would start early in the morning with his horse towing the boat loaded with about 20 tons of clay up the Macclesfield canal. Almost three hours to Marple then onto the Peak Forest canal and spend two hours getting down the 16 locks. A couple more hours to Dukinfield, tie up and assist unloading the clay by hand. Turn the boat, head off back up the Peak Forest canal, two more hours up the Marple flight and back along the Macclesfield to Bollington. A good sixteen hours work; time to knock off! Do it all again in the morning!

The above photo (left) was taken from Sugar Lane canal bridge around 1934. The boat on the left is at the wharf for the Clarence Fireclay mine operated by John Hall. Clay, shale and a small amount of coal was brought from the mine off the fields to the left in tubs or tipped down shoots to the boat. The boat was most likely named Benefactor as this was a regular on this run at this time. The mine closed in 1938.

Notice on the right of the canal the line of telegraph poles. These were a regular sight in the mid-20thC. Each pair of wires (one on each insulator on the pole) provided for one telephone line. The canals were commonly used for this service because they covered large parts of the country and were mostly reasonably straight.

The photo to the right is a similar view from Sugar Lane bridge in 2018. You can just see the chimney of Clarence Mill.

Acknowledgements

Our thanks go to those who researched and discovered the history that is presented in these pages. Please read the full acknowledgement of their remarkable achievement. Unless otherwise noted, the historical pictures are from the Civic Society picture collection at the Discovery Centre .

Your Historic Documents

Please don't chuck out those historic documents and pictures! Find out why here.